History Of Use

Entheogenic Plants

Some medical conditions and psychological disorders entheogenic plants help treat include:

- Pain

- Insomnia

- Suicidal tendencies

- Depression

- End-of-life anxiety

- Substance abuse

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Bipolar and related disorders

- Stress related disorders

- Dissociative disorders

- Somatic symptom disorders

- Eating disorders

- Disruptive disorders

Legality Maps

A complete list of entheogens and psychedelics can be found here.

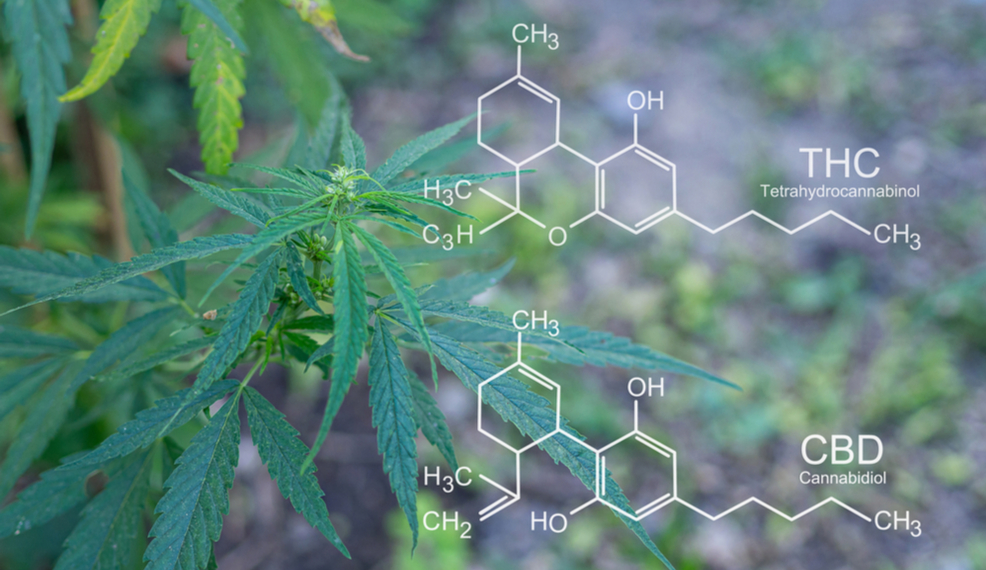

Cannabis

Cannabis is one of the safest substances to consume. It is the most common mind altering psychoactive plant used in the world, and is the only known natural source of the cannabinoids THC and CBD. Cannabis has been used for thousands of years in textiles, medicine, and spiritual practice.

Despite its proven therapeutic benefits, both physiological and psychological, cannabis has been prohibited in most parts of the world since the 20th century and as a result supporting research is lacking. In more recent years, cannabis has been decriminalized and legalized for both medicinal and recreational use in several states in the U.S., Canada, and other parts of the world. With legalization and decriminalization came a massive market for cannabis-based products.

CBD, despite being non-psychoactive, is normally hemp derived following the 2018 Farm Bill and rescheduling of the substance altogether. Because it is non-psychoactive, many people who are hesitant to consume cannabis but want to benefit from it turn to CBD-based products, such as lotions, tinctures, or capsules.

Synthetic versions of CBD and other cannabinoids, such as “spice” and K2, vary widely in chemicals used and effects perceived, and should be taken with caution. Dose does not seem to play a factor in predicting the duration or potency and users may experience adverse side effects, including heart palpitation, chest pains, and possible seizures.

Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is an entheogenic brew or tea that originated in the Amazon Jungle basin. It is commonly made from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and Psychotria viridis (chacruna) leaves, which contain monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and DMT respectively. MAOIs are particularly important as they allow DMT to be orally active by preventing the breakdown of DMT before reaching the blood-brain barrier.

Traditional ayahuasca ceremonies are practiced among indigenous South American tribes, many of which date back to pre-Columbian times and possibly go back to some of the earliest human inhabitants. In more recent years, ayahuasca has become increasingly popular among Westerners for its therapeutic benefits and treatment for depression, mental illnesses, and immune disorders. Due to the religious nature that surrounds an ayahuasca ritual, the legalities on it can be a bit complicated. Many countries, including those that offer ayahuasca retreats, have no specific laws regarding the brew, making the manufacture, possession, and distribution of it a legal gray area.

Another botanical preparation for N,N-DMT consumption is the inhalant version of the ayahuasca plant mixture, called changa. Using the same theory as an ayahuasca brew, changa is a mixture of the MAOI-containing Banisteriopsis caapi vine or Peganum harmala (Syrian rue) and DMT-containing plants or root bark such as Mimosa hostilis (jurema preta) or Acacia confusa. By utilizing the mixture of naturally occurring DMT in plants and the digestive enzyme blocking abilities of MAOIs, DMT is able to be inhaled and pass the blood-brain barrier giving the user an experience similar to ayahuasca but shorter in duration, with all of the characteristic facets of ego death, out of body experiences and overwhelming entheogenic feelings.

DMT

DMT, or N,N-dimethyltryptamine, occurs naturally in many plants and is hypothesized to be endemic to animals as well. It is the active hallucinogenic compound in ayahuasca and establishes the prototypical framework that other psychedelic tryptamines, such as psilocybin, adhere to. Through ayahuasca rituals, DMT has been used for centuries by indigenous tribes for healing and spiritual awakenings ceremonies. Though there is not much formal research on the therapeutic effects of DMT, there are plenty of anecdotal reports expressing the important connection between the substance and self-awareness, as well as powerful personal insights.

Naturally occurring DMT has been found in our brain, blood, and urine, indicating our bodies have the ability to readily metabolize it. According to research, the compound is an important factor in certain processes that take place in our central and peripheral nervous systems. Over the years, studies have also shown that DMT produces an anti-depressant quality that can result in tremendous therapeutic improvements in the well-being of adults.

From 1990 to 1995, American clinical associate and New Mexico professor of psychiatry Rick Strassman led a study on the effects of DMT— the first government-funded clinical research in 20 years on the effects a psychedelic substance has on human subjects. Due to the god- or spirit-like hallucinations and overall religious experience it produced, Strassman dubbed DMT as the “spirit molecule.” In 2000, Strassman published the book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, in which he describes his studies and gives detailed accounts of his sessions with 60 volunteers. It was from this research that many proposed hypotheses were hastily accepted as conclusions, including the connection that endogenous DMT is produced in the pineal gland as well as the rumor that DMT is intrinsically present in every plant and animal on Earth. These assumptions made their way into the mainstream narrative and have since been intertwined with multiple amateur hypotheses concerning everything from bodily production and utilization during endogenous processes, to extremely fringe conjectures of lost knowledge and past societies’ spotlighting of the pineal’s integral role in our species’ history represented through hieroglyphics. Though DMT can be found in a wide variety of organisms and recent research suggests it might be produced in the human brain, both assumptions have yet to be proven correct.

Despite DMT’s powerful healing properties, it has remained illegal throughout the world since the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. DMT is not to be confused with 5-MeO-DMT, another powerful hallucinogenic substance, considering the two tryptamines are in fact quite different. Very rudimentarily put, while both tryptamines produce feelings of interconnectedness and unexplainable spiritual experiences, DMT is known to cause more of a notable visual shift, whereas 5-MeO-DMT produces more of a perceptual schism. The experience of (multiple hits of) DMT can be described as a feeling of euphoria, similar to other tryptamine onsets, with a noticeably swift rush of visual and auditory distortions and hallucinations, geometric and mechanical fractals, intense immersion, and (if enough is consumed) a possible “breaking through” past the initial distortionary onset and into different realms or what seems like piercing the veils of other dimensions. This phenomenon of “breaking through” the fractals points to a higher level of the experience where the possibility of meeting other entities has been reported as far back as the earliest known accounts of ayahuasca use. The effects of these two tryptamines can be described as similar but different, with N,N-DMT having a tendency to overwhelm the senses and be difficult to remember or integrate upon return to baseline.

5-MeO-DMT

5-MeO-DMT is a naturally occurring psychedelic that belongs to the tryptamine family. It can be synthetically produced or found in certain trees and shrubs, usually in tandem bufotenin (5-HO-DMT), however it is most notably found naturally in the venom of the Sonoran Desert Toad (Bufo alvarius). 5-MeO-DMT is also endogenously produced in the body, similar to N,N-DMT, suggesting our innate ability to metabolize and transfuse the molecule through the blood-brain barrier may be inherent to us as mammals. One note of concern regarding the natural production of 5-Meo-DMT is the protected-status of the toad and the impact on its environment may be susceptible to exploitation, with the status of endangered in CA, threatened in NM, and secure in AZ, precautions should be taken when procuring this medicine from reliable sources.

Traditional uses in Central and South America go back centuries. It was first recorded in 1496, when Friar Ramón Pané observed the Taíno people of Hispaniola inhaling “cohoba,” a snuff that contained 5-MeO-DMT; and again in 1737 by Joseph Gumilla, who observed a similar practice in southern Venezuela. In 1936, nearly 200 years later, 5-MeO-DMT was synthesized for the first time by two chemists: Toshio Hoshino and Kenya Shimodaira.

The first modern record of someone extracting and smoking the Sonoran Desert Toad venom was Ken Nelson in the summer of 1983 after being inspired by an article in the August 1981 issue of OMNI magazine. In the article, Dr. Jeanne Runquist had excavated a Cherokee settlement in North Carolina where she found up to 10,000 toad bones and prompted Nelson to begin anthropological and scientific research into the possibility of a psychedelic toad, perhaps used in entheogenic rituals. He eventually identified the overtly glandular anuran Colorado River Toad (Bufo alvarius) as the most likely candidate, and traveled to the Arizona desert during the monsoon season of 1983. Nelson then had the first known modern toad venom extract experience which prompted the writing of the pamphlet Bufo Alvarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert under the pseudonym Albert Most.

In the early 1980s, one could legally order extracted 5-MeO-DMT by mail from the Church of the Tree of Life and the Church of the Toad of Light, the latter of which was founded by Nelson. As recreational use increased throughout the decades, it was eventually declared a Schedule I drug. Today, 5-MeO-DMT is being studied for its therapeutic benefits, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and addiction. It is also a tool for personal growth and spiritual enlightenment. Because of this proliferated use, the toad is facing endangered status and a negative impact on its natural environment. It was in 2019 that researcher and chemist Hamilton Morris expanded and updated Nelson’s pamphlet, with the help of original illustrator Gail Patterson, to include a final page on the synthetic synthesis of 5-MeO-DMT. This reissue was done in honor of Ken Nelson, who passed in late 2019, with all of the proceeds going to toad conservation efforts and Parkinson’s Disease research.

Though sometimes mistaken for DMT, 5-MeO-DMT is known to produce an overwhelmingly strong perceptual shift and immediate onset of a tryptamine high and a visual white light, whilst being immersed quickly into a memory and time distorting “trance” where the user dissociates and dissolves their sense of self/ego much more rapidly than with DMT. It is known to be felt as a very human and religious experience which is remotely shared by the two tryptamines though distinctly different in nature. The trip is said to be less of a visual experience and instead consists of multiple interconnected sensations and an overloading of the psychical senses which can demand the user to submit to the medicine. Experiences include an essence of oneness, feelings of new perspectives, a fuller understanding of mindfulness, gratitude, and a lasting satisfaction of life and contentment in oneself. The experience is said to be the most therapeutic of any psychedelic-assisted therapy, but it is scantly used and relatively unavailable in comparison to psilocybin, LSD, ibogaine or DMT.

Mescaline

Mescaline is the parent compound of the phenethylamine family. It is one of the oldest known naturally occurring psychedelic substances and can be found in the San Pedro (Echinopsis pachanoi) and peyote (Lophophora williamsii) cacti. The ceremonial and ritual uses of these cacti date back thousands of years and originate from native tribes in Texas and New Mexico, including the Tonkawa and Mescalero tribes, among several others. Though these cacti are commonly used for spiritual enlightenment and ritualistic purposes, peyote in particular has been used by the Rarámuri peoples as a topical treatment for wounds and in long-distance endurance foot races.

Mescaline was first isolated in 1897 by Arthur Heffter and synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth. In 1953, famous author Aldous Huxley experimented with mescaline for the first time. Feeling compelled to share his experience, he wrote The Doors of Perception, which was the inspiration behind the name of the famous rock band The Doors. Mescaline has influenced the work of other authors as well, such as Hunter S. Thompson and Carlos Castaneda. The substance is also an important part of chemist Alexander Shulgin’s work. Shulgin used mescaline as a base compound for dozens of synthesized psychedelic phenethylamines. It is even included in his self-rated list of the most important psychedelic phenethylamines— the “magical half-dozen.”

Today, peyote and San Pedro cacti are still primarily used by Mexicans and South Americans. Due to the slow-growing nature of peyote, it is considered an endangered species. The San Pedro cactus, unlike peyote, grows rapidly and self-cultivation is much easier, so it is not considered an endangered species.

Ibogaine

Ibogaine is derived from the root of the Iboga tree (Tabernanthe iboga) and is used in religious ceremonies by the Bwiti religion practiced in West-Central Africa. Though they have been occurring for centuries, it was not until the second half of the 19th century that these ceremonies were observed and reported in the West.

Ibogaine is considered one of the most complex compounds in chemistry. There is almost nothing it cannot do. It hits the same receptors in the brain as LSD, but also has a high affinity to NMDA receptors and produces a ketamine like effect. Ibogaine also releases Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) protein, which is one of the most important proteins needed to treat Parkinson’s.

In a therapeutic setting, ibogaine is mostly used to treat alcohol and drug addiction and is known to eliminate or greatly reduce physical withdrawal symptoms, with some users reporting permanent eradication of withdrawals after one treatment session. Despite these promising results, it was declared a Schedule I drug during the 1960s. Recently, a U.S.-based pharmaceutical company, DemeRx, has started to work on the development of ibogaine and noribogaine (the main psychoactive metabolite in ibogaine) into oral, non-addicting drugs for opioid dependence.

kratom

Mitragyna speciosa, commonly known as kratom, is an evergreen tree native to the jungles of Southeast Asia. It grows wild in certain areas in the Pacific Rim, such as central and southern Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Myanmar, where it has been used as traditional medicine since at least the 19th century. The main psychoactive compounds found in the tree’s leaves are 7-hydroxymitragynine and mitragynine– a compound often compared to psilocybin because of its 4-substitute structure.

Experts are unsure of when people first started to use kratom but it is thought to be an ancient practice. It was first tested on humans in 1932 and was likened to cocaine for its stimulant effects on the central nervous system. When taken in small doses, it can be used to substitute caffeine, allowing users to feel the effects of coffee without a caffeine crash. In large doses, it can mimic the effects of opiates and can deliver a sedative effect. For the most part, people generally report feeling energetic, sociable, motivated, and euphoric. Though there are no mainstream medical uses for kratom, it has been known to relieve pain, soothe fevers, manage diabetes, and, most notably, treat addiction. Some experts even believe it can replace methadone for heroin addiction. Despite growing interest in kratom’s medical potential, places like Thailand and Australia banned it by the early 2000s. In the United States, kratom remains legal thanks to advocacy and campaign groups.