History Of Use

Brief History of Fungi

Before we can understand the cultural significance of psilocybin mushrooms historically and contemporarily, as well as their future in the medical field, we must first understand the important role fungi have within the context of our environment and the history of this planet. On a very basic, but incredibly crucial level, fungi break-down organic matter and transmute it into life-giving soil. As this planet evolved, fungi provided soil which propagated the plants and trees that produce much of the oxygen we breathe. The fungal kingdom in turn relies on plant species for survival in one way or another due to their synergistic connection to the mycelial network of the earth. From the first evolutionary symbiosis between algae and moss, to catalyzing the development of leafy plants and their ability to inhabit landscapes further inland, fungi have incorporated themselves strategically into the least energetically-taxing, but most beneficial, relationship with their ecosystem and the rest of nature.

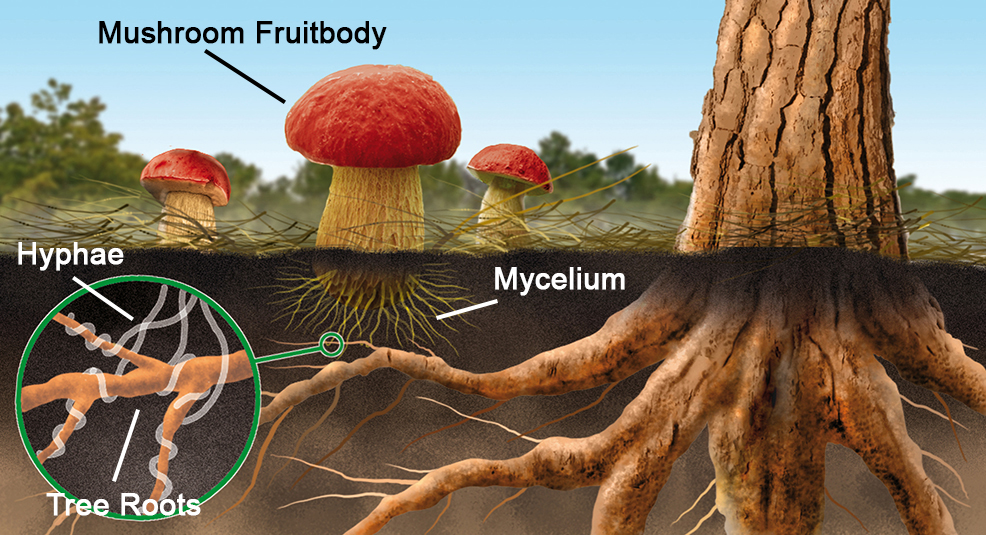

Seemingly by design, fungi live in an interconnected world and exist as another mode of life on this planet. With a lack of physical gender (though thousands of sexes manifest within the mycological universe) and their stationary posture, fungi visually appear more related to plants than animals. However, utilization of oxygen for respiration, heterotrophic subsistence on organic material as opposed to photosynthesis, as well as a myriad of other abnormal similarities, make fungi more appropriately related to animals, though they are in their own kingdom entirely. It is a common misconception that fungi are merely the sprouted mushrooms (aka fruit bodies). Rather, fungi exist as a mass branching mycelial network of hyphae, constantly existing as an interconnected organism. In fact, fungi helped plants move from nutrient rich waters in the first place and onto a land environment, nutrient poor and torrid at the time. Working in an exchange for sugars and minerals, plants and fungi were able to set the stage for the animal kingdom to inherit lush, fertile landmasses.

Organisms in the kingdom Fungi have often been referred to as chemical factories, as they are capable on the whole of synthesizing a vast array of molecules, ranging from medicine to poison, jet fuel, digestion enzymes and psychedelic compounds. The common archaeological conception of psilocybin-producing species is that it was an evolutionary development that led to an advantage as a defense mechanism, though that is still a topic of debate. There is much speculation and opinion that some kind of intelligent agent, perhaps an underlying theoretical “entity” or what our understanding of such a consciousness would constitute, is inherent to the psychoactive compound or even the mushroom itself. This further goes to suggest that one or the other was intentionally put on Earth (possibly as some form of galactic panspermia) as a tool or bridge of sorts; a means of communication across realities or paradigms. There is, however, a lack of tangible supporting evidence for fringe mystical elucidations from strictly scientific perspectives.

Modern Cultural Impact

Psilocybin (4-PO-DMT), the primary psychoactive compound in “magic” mushrooms, has a very rich history. From indigenous tribes and traditional ceremonies to the counterculture movement in the 60s and modern medical research, psilocybin mushrooms have imparted their value through a wide array of cultural contexts.

Images of what archaeologists believe to be psilocybin mushrooms can be traced back thousands of years in sacred art and cave drawings across multiple continents and cultures. This suggests that the Psilocybe genus has appeared on nearly every continent since ancient times. They were associated with ceremonial traditions, spiritual enlightenment, and holistic healing practiced by indigenous tribes from all over the world long before they became synonymous with negative stereotypes, and ultimately outlawed across much of the modern world.

In 1957, the Vice President of J.P. Morgan, R. Gordon Wasson, published his famous essay in Life Magazine, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.” He recounted his experience using the substance under the guidance of a well-known and highly respected shaman, Maria Sabina. Wasson’s essay inadvertently kick-started the psychedelic movement, and he essentially transformed the hallucinogenic mushroom from a sacred fungi to a worldwide curiosity.

Shortly after Wasson published his essay, the small indigenous Mazatec village of Huautla de Jiménez where Sabina is from became flooded with musicians, artists, writers, and psychologists seeking out Sabina’s “velardas,” or mushroom healing rituals. These included the likes of Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Alvaro Estrada, and Timothy Leary among others.

Though foreigners would turn to Sabina for personal enlightenment and in an effort to “find God,” she would explain to them that her ceremonies were for healing purposes and curing the illnesses her community faced. After foreigners were turned away, they often found Sabina’s fellow Mazatecs selling the mushrooms as a means to support their families. This eventually led to more people traveling to Sabina’s hometown and misusing the sacred mushrooms.

Wasson may have sparked interest, but it was psychedelic advocates like Timothy Leary that really helped raise awareness in the West about the benefits of these substances. After Leary, who was once a clinical psychologist at Harvard University, read Wasson’s essay, he and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) created the Harvard Psilocybin Project. Their group conducted a series of psychedelic experiments with psilocybin and other psychedelics. The purpose of these experiments was to raise awareness surrounding the healing properties of entheogenic substances. They were fired shortly after, but they continued their work and went on to pioneer much of the research we still reference today. The project’s work and advocacy became a major figure in the counterculture movement, and influenced many aspects of it. Between Wasson’s essay and Leary’s project, people became so intrigued with psychedelics that it drove them to create new genres and forms of music, literature, and art. Psychedelic rock gave a voice to a generation; some of the most important and influential pieces of American literature came out of psychedelic literature, or “trip lit;” and psychedelic art encouraged freeing and self-expressive paintings, photos, posters, and underground zines.

Some of the most influential authors from this era were the Beatniks— a term coined by Jack Kerouac in 1948. This group consisted of authors, poets, and artists who rejected and challenged conventional norms, many of whom brushed elbows with Leary and other brazen and outspoken researchers. Much of the beatnik literature was anti-conformist, cathartic, and often about their psychedelic experiences on a number of substances, including psilocybin, LSD, mescaline, and even more obscure psychedelics of the day, such as AMT. In 1957, Kerouac (the “King of the Beats”), published his most famous novel On the Road. Although it is a piece of fiction, it was heavily influenced by Kerouac’s own life and beatnik culture, and introduced traditional Americans to a world they otherwise would not have known. It was also an inspiration to the author Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and his Merry Band of Pranksters.

In 1964, Kesey purchased a 25-year-old bus and named it Furthur. He revamped it to fit the bright, colorful, groovy decor of the time, complete with bunk beds, a small kitchen, and, of course, a custom sound system. After he read On the Road, he became so inspired that he and his friends, known as the “Merry Band of Pranksters,” traveled across America in Furthur. The bus soon became a symbol of youth, rebellion, and anti-establishment. They would often pick up locals in search of alternative lifestyles, and threw parties with LSD-laced Kool-Aid known as the Acid Tests. These famous parties sometimes included bands like the Grateful Dead and motorcycle gangs like the infamous Hells Angels. The Acid Tests also inspired the UK’s 14-Hour Technicolor Dream, where psychedelic rock band Pink Floyd and Pete Townshend of The Who performed. The crowd of attendees included Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono, before the latter two had met.

In 1968, Kesey, the Merry Pranksters, and Furthur became the subject of Tom Wolfe’s nonfiction novel The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Similar to how Kerouac’s novel depicted Beatnik culture, Wolfe’s novel showcased the height of the counterculture movement. Wolfe was a pioneer of a literary technique called New Journalism. Much like the beatniks and hippies, this technique broke all traditional rules. It was a very unorthodox and intimate style of writing: rather than readers feeling like they are on the outside looking in, New Journalism allowed one to fully immerse themselves in the world they read about. This was particularly important for authors like Wolfe who wanted to show America that there is more than one way to live. Wolfe interviewed Kesey for a few weeks to gather firsthand accounts of him, the Merry Pranksters, and Furthur’s adventures, allowing him to keep the details as accurate as possible. The novel includes a revolving cast of characters, such as Neal Cassady— a beatnik who drove Furthur and is featured in Kerouac’s novel as Dean Moriarty— Ken Babbs, Timothy Leary and famous musician Jerry Garcia. Electric Kool-Aid starts with Kesey gathering his followers and ends with Furthur and the Merry Pranksters at Woodstock; as the book travels through time so does the audience. Published in 1968, the book serves as an accurate depiction of the growth of the counterculture movement. The New York Times has even considered the work a piece of art for its time and touts it as an essential book about hippie culture.

Many of the events Furthur and thousands of others traveled to were discussed openly on underground radio stations and in magazines. One of the most popular underground magazines at the time was OZ, which was read by nearly 80,000 readers during its peak circulation. OZ was originally published in Sydney, Australia, but became the subject of one of Britain’s longest obscenity trials. The underground magazine covered a wide variety of controversial topics, from back-street abortions to contempt for the Australian government. OZ heavily encouraged and supported left-wing politics, sexual liberation, psychedelics, and other anti-establishment movements. So it was no surprise when Britain’s government challenged their freedom of speech by charging them with “conspiring to corrupt public morals”— a charge with no limits. Although they were found guilty of smaller charges, their case was eventually granted an appeal on the basis that the judge misled the jury. They were released from prison but had to agree to stop working for OZ. By that time, OZ had already left its mark on the exploding underground magazine world. It was through OZ and other underground magazines that controversial topics were freely talked about and quintessential psychedelic events were advertised, such as the Human Be-In.

In 1967, Leary famously preached to a crowd of thousands at the Human Be-In, “turn on, tune in, drop out,” this slogan would ignite and define the San Francisco Summer of Love and the counterculture movement made famous by recounts from famous authors like Hunter S. Thompson and William S. Burroughs. The event was hosted by famous American artist Michael Bowen and took place at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. It included influential speakers, poets, and musicians, like Alan Watts, Ram Dass, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, and the Grateful Dead. Dubbed “The Gathering of Tribes,” the event pulled in between 20,000 to 30,000 people from all over who shared similar views on activism. It called on the attendees to question authority and quickly became a symbol of the rising youth movement. The Human Be-In event was a catalyst for the Summer of Love all over the world, and went on to influence many other “-Ins,” including “Yip-In,” “Love-In,” and “Bed-In,” as well as the music festival of all music festivals: Woodstock. Unfortunately, it was events like these that eventually led to the war on drugs and the demise of psychedelic research. With the implementation of the Controlled Substances Act in 1971, the American government heavily restricted the use of psychedelic substances, and put a screeching halt on all medical research.

There was a massive resurgence of psychedelic interest in the 1990s when ethnobotanist Terence McKenna began to advocate for the responsible use of entheogens. Terence and his brother, Dennis, became famous for developing a method for growing psilocybin mushrooms using spores from the Amazon. They were the first to pioneer this technique, which could be done at home using basic kitchen utensils. For the first time, people were able to cultivate their own entheogens from home.

Terence and Dennis McKenna proposed the “Stoned-Ape Theory” in Terence’s 1992 book, Food of the Gods. It essentially states that colonies of Homo erectus discovered psilocybin-containing mushrooms growing in ancient grasslands, and their consumption of them over generations played an integral role in the development of what would become the larger-brained Homo sapiens, as well as the resultant phenomenon of culture. This may have manifested as increased visual and mental acuity as well as increased physical stamina, all of which potentially enabled more productive and efficient strategies for hunting larger and more nutrient-rich game to further fuel our evolution. Additionally, it may have helped foster a greater sense of community among early humans, eventually leading to the earliest forms of civilization. Although this theory does not have a lot of support behind it, it is an area of interest for many researchers.

Today, despite psilocybin mushrooms being classified as a Schedule I drug, the psychedelic fungi has become more accepted and researched in the medical field. In recent years, psilocybin has been clinically studied and tested by highly accredited institutions and foundations to treat a wide range of physical and psychological ailments, ranging from PTSD and OCD to addiction and depression.

With further education, research, and testing, we can expect to see the continuation of decriminalization, demystification, and overall acceptance of the healing and spiritual effects of psilocybin.

Medical Benefits

Psilocybin is primarily known for its psychedelic effects, but since the 1960s it has been studied for its medicinal properties. In recent years, experts have acknowledged and commended psilocybin’s ability to help treat a wide variety of medical conditions, including anxiety, depression, cluster headaches, substance addiction, and OCD.

Anxiety and depression are two of the leading areas of psilocybin treatment research. One of the most well-known cases is a 2011 pilot study that tested the effects of psilocybin on 12 patients with advanced-stage cancer who were experiencing end-of-life anxiety and depression— the first study of its kind in 35 years. The results showed a significant improvement in levels of anxiety and depression in the patients for up to 6 months after the trial.

Each patient’s depression was measured on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scale; mood states were measured on the Profile of Mood States (POMS) scale; and anxiety was measured according to the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scale. BDI measurements reduced by nearly 30% and sustained this level at the 6-month follow-up. The POMS results increased one day before psilocybin treatment, indicating low mood levels. However, this dramatically decreased 6 hours post-ingestion. Increased mood levels remained about the same from the 6 hour mark to up to 2 weeks after treatment. Lastly, STAI trends showed a decrease in levels of anxiety 6 hours after psilocybin administration. Though it was not a significant decrease, low levels of anxiety were sustained for the entire 6 months. This study was eventually granted Phase II status by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In an open-study from 2017, researchers at Imperial London College tested psilocybin therapy on 12 patients with treatment-resistant major depression, and offered psychological support before, during, and after each psilocybin treatment. Depression was significantly reduced in nearly every patient one week after their second dose, with 8 out of 12 scoring 9 or under on the BDI scale, indicating zero symptoms of depression. After the 3 month mark, 5 patients reported feeling depression-free, and 4 others reduced the rating of their depression from “Severe” to “Mild or Moderate.”

Cluster headaches, sometimes referred to as “suicide headaches,” are extremely painful and disruptive migraines. They can occur several times a day for weeks or months followed by a period without headaches. When taken at a sub-perceptual dose, psilocybin can abort attacks, terminate a cycle, or extend the sufferer’s remission period, and has proven to be an effective remedy for those who are treatment-resistant.

Psilocybin research and therapy have also been efficacious in the treatment of drug and alcohol addiction. Studies show that when alcohol-dependent patients include psilocybin as part of an assisted treatment plan, they are more likely to reduce the amount they drink or completely abstain. In 2015, researchers from the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center conducted a single-group proof-of-concept study to look into the effects psilocybin has on alcohol dependence. Psilocybin was administered during a supervised session and included motivational enhancement therapy in conjunction with therapy sessions dedicated to preparation and post-treatment discussion. The results showed that abstinence levels significantly increased post-treatment and maintained the same at the 36-week follow-up. Results also predicted a decrease in cravings. Tobacco smokers who include psilocybin in their treatment plan have experienced similar results.

Psilocybin has also been known to help treat or significantly reduce symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). In a small study by MAPS, 9 subjects who did not respond to conventional serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) drug therapy were administered over 20 psilocybin treatments. The results showed that each patient, during at least one or more sessions, saw a reduction in OCD symptoms ranging from 23% to 100% when treated with psilocybin.

Though criminalization of psilocybin mushrooms has made research and testing a long and difficult process, hospitals, foundations, and scientists from around the world are recognizing how powerful and important these interventions are for the mental and physical health of all of humankind. With the decriminalization of psilocybin mushrooms comes a vast wealth of research and knowledge that opens doors to a healthier and more positive world.